by Mike Niemeyer, FoSF Board President

Did you know that the original vision for Silver Falls as a public park included the headwaters of Silver Creek and relative tributaries? Today the waters that flow through our iconic waterfalls originate on private forest land. Concerns about protecting the Park’s watershed are not new. Here is an excerpt of a letter from Sam Boardman, the first Oregon Parks superintendent, to is successor: (Emphasis mine)

“One thing should be noted that is outstanding and I doubt if it can be duplicated in the United States, wherein you have fifteen waterfalls in an area of a mile and a quarter by three miles and a quarter. The composition of your park is mainly of waterfalls. The life of your park is dependent on water. You do not own the watershed upon which the park is dependent. This watershed must be protected if you would keep the scenic values of your waterfalls, the financial investment you have in the park. In the beginning of the R.D.P., when land was being purchased, we had an option on nine thousand acres of the watershed for $9,000. The National Park Service was buying the land but I was unable to convince them that the watershed should be bought. The Longview Fibre Company now owns the property, paying $200,000 for it. They are making a tree farm out of it, and when matured, will cut only in a block form. Selective cutting as it were. You should contact the personnel of this firm that they may understand your position and their cooperation secured in the matter.”

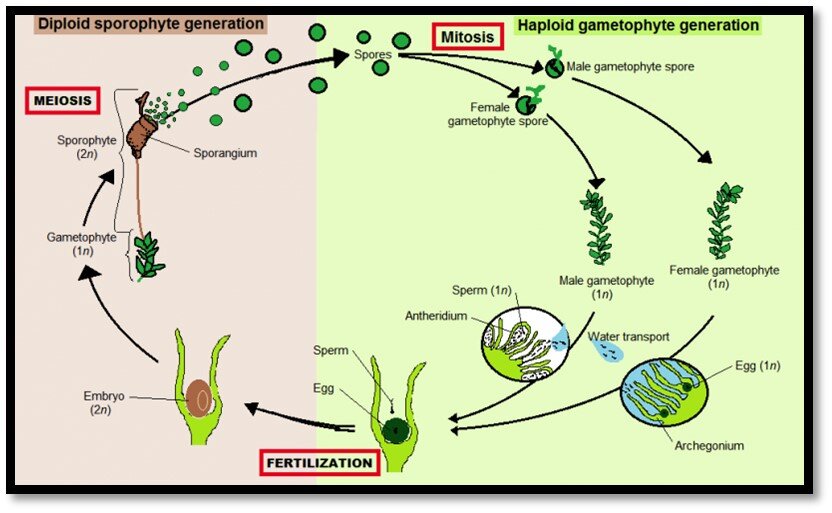

Green area indicates State Park area (2024)

Blue area indicates area inclusive of headwaters of watershed

-

A) North Fork Silver Creek

B) Little North Fork Silver Creek

C) South Fork Silver Creek

D) Howard Creek

E) Smith Creek

Silver Falls State Park is located within the boundaries of the Pudding River Watershed, which extends north/northwest to include 528 square miles and 48 rivers and streams! Click here for more information about the Pudding River Watershed Council and how to get involved supporting efforts to protect these natural resources.